Brewing the Perfect Cup- Filter Coffee through Percolation Theory

Explore how the principles of percolation shape the journey from grounds to the perfect brew.

[This article has been written for The Network Pages]

Coffee brewing is more than just a morning ritual—it’s a fascinating interplay of physics, chemistry, art, and mathematics. While different coffee brewing methods require different techniques, at the heart of this process it involves either water or steam seeping through ground coffee beans.

In this article, we’ll filter the science through the lens of a simple question: what makes a cup of coffee great? From understanding why grind size matters to appreciating the balance between under-extraction and over-extraction, we’ll explore how the principles of percolation influence every sip you take. Whether you’re a scientist, a coffee enthusiast, or simply curious about the science behind your brew, this is your guide to brewing perfection.

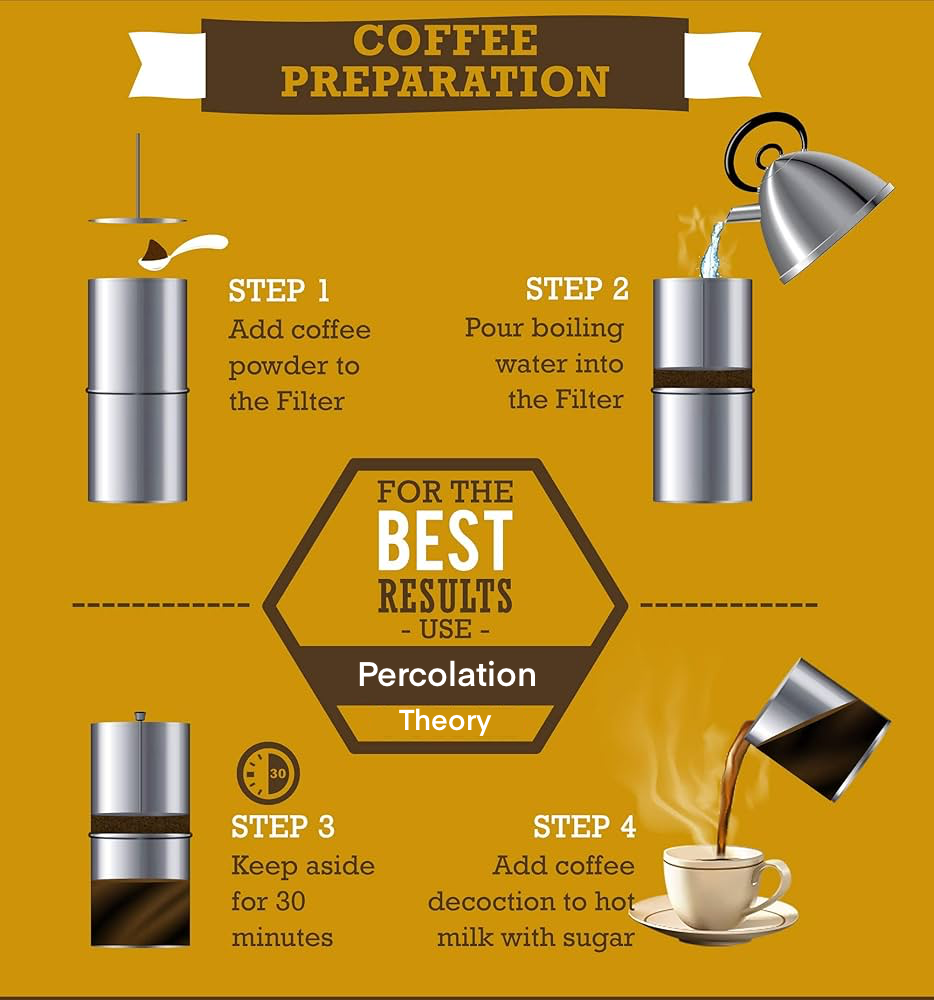

Let’s make things concrete. In this post we will focus on brewing drip coffee, or pour-over filter coffee. This is done by pouring hot water over ground coffee beans, placed in a paper filter within a funnel. The water seeps through the powder, passes through the filter and collects in a container beneath. This is shown in the figure below.

The dynamic of the movement of water through ground coffee beans is strikingly explained by percolation theory. Percolation theory, introduced by Broadbent and Hammersley in 1957, studies the flow of fluid within a porous medium. Over the years, it has been used and applied to several other fields, including information dissemination in communication networks, the spread of an infection through an orchard, rumour spreading in online social networks, among others. Naturally, it forms a palatable model to describe the brewing of coffee as well. Here is how it is done.

Coffee brewing and percolation

Think of the particles of the ground coffee to be arranged like a hexagonal lattice as shown in Fig. 3. When water is poured, the granules on the top layer come in contact with it. The water dissolves the caffeine and other soluble components within the coffee granules giving it the aroma. In other words, water extracts coffee from the granule. The water makes its way to the next layer where the coffee extraction procedure repeats. This process continues as the caffeinated water makes its way through the coffee bed, passes through the filter and collects in the container below. A fresh cup of coffee is ready for you to be relished.

Fig. 3: A hexagonal lattice coffee bed.

However the process is not as simple. It might so happen that a granule of coffee absorbs the water and it does not pass to the next layer. After all, the amount of coffee you get after brewing is not exactly the same as the amount of water you poured in, right? This absorption could be a result of numerous factors such as the composition of the granule, its size or shape, the amount of water etc. While these are individually not easy to account for, mathematicians model coffee dissolution within a granule as an event of chance. They assume that each granule allows the water to pass through with probability \(p\), and does not allow it (or, absorbs it) with probability \(1-p\). It turns out that this simple modelling abstraction helps to capture various aspects of fluid propagation in porous media, or in our case, gives pointers for coffee brewing.

To understand this better, let us assume that each granule has a coin that lands heads half of the time and tails the remaining half. All the granules in our hexagonal coffee bed toss their respective coins before the water is poured. A granule decides to let water pass through it (along with giving it some dissolved caffeine) if its coin lands heads; it does not allow water if the coin lands tails. Our coffee bed will look as in Fig. 4 where the brown circles are granules that allow water through them and the empty ones do not. In percolation theory, the brown circles are referred to as open sites and the empty circles are called closed sites.

Grind size

The percolation model provides a structured way to incorporate multiple variables in the coffee brewing process. To illustrate, consider the process of grinding coffee, arguably the most important factor influencing the taste of your brew. Grinding breaks roasted coffee beans into smaller granules, increasing their surface area. The finer the grind, the greater the surface area exposed to water, allowing for more efficient extraction of the compounds responsible for coffee’s flavour.

In the percolation model, grind size can be represented by adjusting the probability parameter \(p\). Previously, we assumed each granule had an equal chance of allowing water to pass through, corresponding to \(p=0.5\). Instead, if the granules used a coin that lands heads with probability \(p = 0.75\) (and tails with probability \(1-p=0.25\)), water would have a higher likelihood of dissolving caffeine and other solubles within each granule. This mirrors the effect of a finer grind, where more surface area is in contact with water, leading to faster extraction and a stronger brew. Thus, a finer grind corresponds to a higher value of \(p\). In turn, a higher \(p\) represents a larger number of open sites in the percolation model.

Top-bottom crossings

Fig. 5: Blue lines indicate top-bottom crossings

With a solid mathematical model for coffee extraction, we can now explore when it yields good coffee, offering insight into the key parameters we can adjust during brewing for a more flavourful coffee. In our model, coffee flows through the coffee bed if there is a connected path of open sites from the top layer to the bottom, as shown in Fig. 5. In percolation theory, this is known as a top-bottom crossing (read as, top-to-bottom crossing). Ideally, we want to maximize the number of such paths to enhance extraction.

Fig. 6: Effect of the aspect ratio of the coffee bed.

To understand top-bottom crossings, let us picture two separate coffee beds; one that is deep and narrow, and another that is wide and shallow. If the bed is deep and narrow, it would be difficult for water to seep through, since granules at every layer have to let water pass through them. On the other hand, if the bed is wide and shallow, there could be numerous pathways for the water on top to seep through to the bottom. Thus, intuition dictates that it is easier for water to flow from the top to the bottom in the latter scenario. Indeed, looking at the percolation model in Fig. 6, this is clearly evident since there are a lot more top-bottom crossings when the coffee bed is wide and shallow. However, if the bed is too shallow then there is not enough caffeine to extract and we obtain a light (not so strong) coffee. From this discussion, it is evident that the presence of top-bottom crossings is not only governed by the value of the probability \(p\) but also by the aspect ratio of the coffee bed.

Top-bottom crossings in the percolation model were studied by Russo in 1981, and Seymour and Welsh in 1978. In their research, now popular as the RSW theorem, they establish that when the probability \(p\) is larger than a threshold \(p_c\), the probability of there being a top-bottom crossing is close to \(1\) for large enough lattice sizes of appropriate aspect ratio. The constant \(p_c\) is called the critical probability of percolation and is equal to \(\frac{1}{2}\) for the hexagonal lattice. Thus, we can expect to have top-bottom crossings and therefore better extraction when \(p>\frac{1}{2}\) on coffee beds that are neither too shallow nor too deep. As a takeaway, we now have another parameter–the aspect ratio– along with the grind size that we can vary to make our coffee taste better.

In conclusion

Practically, the aspect ratio of the coffee bed is determined by the amount of ground coffee you use while brewing. This is fairly easy to perfect by looking at the strength of the brewed coffee, or the dryness of the bed after brewing. Choosing the right grind size however, is more intricate. While finer grind size can provide stronger coffee, grinding the coffee very fine results in over-extraction giving a bitter taste. In our percolation model, the grind size was captured using the probability \(p\). However, numerous other parameters such as coffee to water ratio, water temperature, brewing duration etc. also affect the parameter \(p\). While a general understanding of how these variables alter your coffee is known, a theoretical validation from percolation theory is still pending. For researchers like me, it forms a self-sustaining cycle: better coffee helps me do better research in percolation theory which in turn helps to improve my coffee. So the next time you enjoy a sip of delicious coffee, spare a thought to the numerous researchers of percolation theory who are in the quest of explaining your happiness.

References

[1] James Hoffman, “The world atlas of coffee”.

[2] Jason Scheltus,”Coffee from bean to the perfect brew”, Liquid Education.

[3] Shawn Steiman, “The little coffee know-it-all”.

[4] Maxwell Colonna-Dashwood, “The coffee dictionary”.

P.S.: The author would like to thank de Bibliotheek Eindhoven cafe for their amazing coffees and an excellent collection of books on coffee brewing using which this article was mostly written.